Mississauga and Historic Surveys – Part 1

/Augustus Jones - survey diary excerpt from 1796 showing names of creeks and rivers

Full and honest disclaimer: I love surveys and maps. Talking about historic cadastral surveys, reading through early surveyor diaries, and looking at early survey plans and maps can lead me down rabbit holes for days. The way land use was planned, surveyed, parcelled, with rights-of-way established, farm lots created, and waterpower sites identified is utterly fascinating to me. I also recognized that not everyone shares this fascination, but you will have to indulge me a bit on this article.

Mississauga is a bit like an onion – there are many layers – layers upon layers, with surveys on top of surveys. The thing about surveys is that when they are completed, they never really leave us. They just get layered with other surveys. In part, they define the geographic and human landscape; they create borders and roads but are also seldom seen. The vital role surveys have played (and continue to play) in historic and modern Mississauga often goes unseen. However, decisions made in almost every historic survey that I have referenced in Mississauga can still be seen in some fashion on our landscape today – in some cases over 200 years later.

For Mississauga, settlement-era surveys, the first proverbial link the land-use planning chain, roughly date between 1796 and 1914. But surveys are continual, and we will focus on some of the major historic surveys, and surveyors, that, in my mind, have helped to share the physical spaces in our city today.

Augustus Jones

But first, lets chat is broad terms about the survey process. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, surveying is the art and science of measuring land. More precisely, it is “a means of making relatively large-scale, accurate measurements of the Earth’s surface.” The Office of the Surveyor General for Upper Canada came to be with the passing of the Constitutional Act of 1791. The Surveyor General was responsible for surveying, maintaining, and selling Crown lands in the province (via land grants and leases), and would report to the Lieutenant-Governor and the Legislative Assembly. In the office of the Surveyor General were several Deputy Surveyors and Clerks. The Surveyor General of Canada lists an apt description of the survey process:

“The physical act of surveying was a difficult one, and required a team of around eight to ten men per surveyor, including two chain bearers (used to determine measurements) and axemen to clear paths. The surveyors were required to keep both diaries and field books outlining their operations, and taking note of characteristics such as vegetation, soil type, topography, and the suitability of the land for agriculture. Upon the completion of a survey, the notes and other records were handed to the Office of the Surveyor General, where draftsmen or surveyors would assemble finished plans based on the material. The maps created by this office established a visual standard, including the use of coloured inks for specific areas (red ink for Crown reserves; black ink for Clergy reserves; blue for water; yellow-green for swamps) and the units of measurement.”

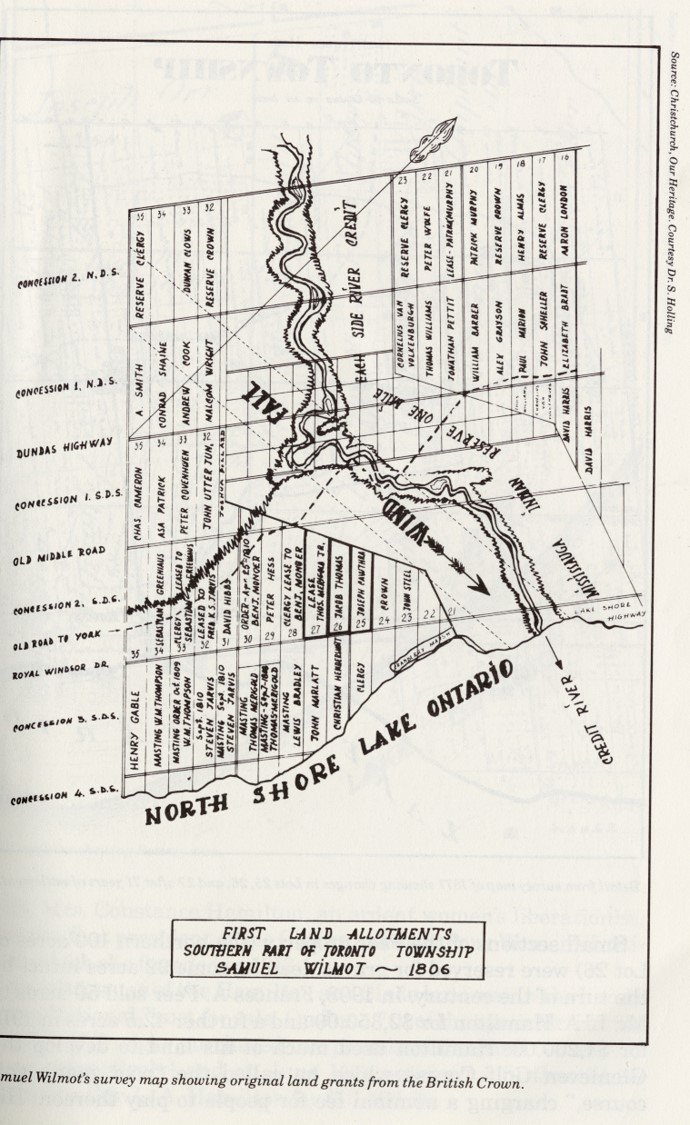

Crop from 1806 Wilmot Survey showing first land grants

The first historic survey to impact Mississauga was that of Dundas Street, which was laid out through this area in 1796, in part following an existing Indigenous route of travel. The surveyor was Augustus Jones (1757-1836), ably assisted by the Queen’s Rangers. Dundas Street, our oldest continuous route of travel in our city, formed the east-west base line for all that would follow.

Following the signing of Treaty 14 with the Indigenous Mississaugas of the Credit (the Head of the Lake Treaty) in 1806, surveyor Samuel Street Wilmot (1773-1856) was charged with surveying the newly acquired lands.

The majority of Mississauga was initially known as Toronto Township and was divided into three primary surveys: the “Old Survey” / Wilmot Survey (1806), “New Survey” / Bristol Survey (1819) and the Credit Reserve (1820-21). There were subsequent survey layers over time, establishing villages within Toronto Township.

Queens Rangers surveying and clearing Dundas Street by CW Jefferys

The Old Survey includes all lands from the Lake Ontario shoreline to Eglinton Avenue, from Winston Churchill Boulevard to Etobicoke Creek, excluding land one-mile each side of the Credit River, which was set aside as an Indian Reserve. Lots within the Old Survey were organized as “single-front” 200-acre lots (long rectangles). Dundas Street is the dividing point, with two concessions being organized North of Dundas Street (NDS) and four concessions South of Dundas Street (SDS). Some of the concessions South of Dundas Street are considered “broken frontage” due to the irregularity of the shoreline. Lots are numbered from East to West, with Lot 1 beginning at the Etobicoke Creek.

The New Survey comprises all lands North of Eglinton Avenue, between the modern roads of Winston Churchill Boulevard and Airport Road and was surveyed as “double-front” 200-acre lots, which were often patented in ½ lots of 100 acres each. Concessions were laid out East and West of Hurontario Street. Lots are numbered from South to North, with Lot 1 beginning North of modern Eglinton Avenue. The New Survey also includes all of modern Brampton and Caledon.

Samuel Street Wilmot

The Credit Reserve lands comprise lands within a 1-mile strip along both sides of the Credit River between the waterfront and modern Eglinton Avenue. The Credit Reserve was divided into several parts over periods of time. The First Part consists of Ranges 1 and 2 North of Dundas Street (NDS) and Ranges 1 and 2 South of Dundas Street (SDS). These ranges were divided into 50-acre lots, and other sizes, and are part of the lands known as the “Racey Tract”. Lots are numbered from West to East. Situated North of Range 2 NDS are Ranges 3 through 5 NDS, also running West to East. This area is known as the “Credit Reserve”. On the South side of Dundas Street, south of Range 2, SDS, was another division referred to as the “Credit Indian Reserve”. These lands were also divided into Ranges 1 through 3. The lots for these Ranges run East to West. In this division, Range 1 is the most southerly, and Range 3 abuts the south side of the Range 2 from the Racey Tract. The closest Range to Lake Ontario is known as a Broken Range because of the irregularity of the shoreline.

Also, part of modern Mississauga is an area that was once part of Trafalgar Township within Halton County, and is bounded by Dundas Street, Winston Churchill Boulevard, Ninth Line and Steeles Avenue, this was historically part of Trafalgar Township in Halton County.

The land from Dundas Street to Eglinton Avenue was part of the 200-acre lots arranged in the Old Survey. These are arranged in Concessions 1 & 2, North of Dundas Street, and Lots 1-5 running west from Winston Churchill Boulevard. Land north of Eglinton Avenue was surveyed into 200-acre lots within Concession 9 (between Ninth Line and Tenth Line) and into 90-acre lots within Concession 10 (between Tenth Line and Winston Churchill Boulevard).

Clear as mud, right? Now that we have moved past the broad description of historic land division, a future article will look at the individual surveys, and at the surveyors who shaped them.