Mississauga's connection to The Spanish Flu

/This too shall pass. As we are all challenged today by the COVID-19 virus, the Way Back Wednesday series will look back at past epidemics and health challenges, with a particular focus on those individuals who sought to aid the sick, and on how our landscape remembers those past times.

Apart but together, please help us capture the story of how COVID-19 pandemic has affected you here in Mississauga. Please share stories and images at history@heritagemississauga.com or https://www.facebook.com/HeritageMississauga

#ApartTogether

As we come to terms with life in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, comparisons have been drawn to the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-20. There really are no other recent parallels of a similar magnitude, but our understanding of what transpired 100 years ago is, to put it lightly, not at the forefront of our collective knowledge. After all, there is no living memory of that time, and what has been recorded on it is piecemeal. However, as we learn more about our current challenges, and we hear warnings of the second wave that is sure to come amidst our struggle to reopen, interest in what happened during the Spanish Flu pandemic has grown.

In Canada, the disease arrived at the port cities of Québec City, Montréal, and Halifax, and quickly spread westward. The ongoing war effort at home, combined with Armistice Day gatherings and returning of soldiers, were instrumental in the spread of the disease. The Spanish Flu arrived on our doorstep here in historic Mississauga in the early fall of 1918. Worry, fear and panic, accompanied by medical advice, public closures, and recommendations for face coverings followed quickly in October. In Peel, as cases increased, further measures for closures and restrictions were recommended. In local terms, we were hardest hit in the winter of 1918-19, and then it waned. But as life began to find the new normal, the virus roared back in the spring of 1919, before gradually petering out in early 1920. The virus was deadly, and spread rapidly, the like of which had not been seen before. When looking at our local history, I am drawn to a large gathering held in Port Credit in August of 1919 at the Hobberlin Estate to honour returning soldiers. One cannot help but wonder if this gathering might have contributed to the spread of the virus.

The immediate response, both nationally and locally, proved to be inadequate, quarantine measures were difficult to impose and oversee, and the lack of coordinated efforts from health authorities led to the medical community quickly becoming overwhelmed: “Municipal and provincial authorities tried to save lives by prohibiting public gatherings and by isolating the sick, but these provisions had little effect. As the rates of infection grew, the number of healthy workers declined. Before long, the Canadian economy was paralyzed. Health care professionals were perhaps the hardest hit.”

The statistics are unclear, as many doctors were often at a loss on how to diagnose, let alone treat, those afflicted. Estimates of those who lost their lives varied greatly. In Ontario, the Registrar General listed 10,000 fatalities, while the Department of Public Health listed 4000 fatalities. In terms of Peel County, it is estimated that the fatalities due to the Spanish Flu were somewhere between 50 and 600. Why the discrepancy? The cause of death for many who died were identified and reported per the symptom, such pneumonia, rather than linked to the Spanish Flu specifically. A brief look a few years ago at cemetery records listing deaths (burials), cross-referenced with death certificates where available, from 1918-1919 suggests that the number of fatalities in historic Mississauga alone may be more than 100. These numbers may feel like they are overshadowed by what we know of those afflicted by COVID-19 today, but the parallels are there, albeit with a higher percentage of fatalities per capita in 1918-20 than we are currently seeing today.

With no vaccine or effective treatment, the Spanish Flu spread to every country around the world, and it came in multiple waves. The first wave was in the spring of 1918, and hit Europe and Russia. The second wave was in the fall of 1918 as it spread through the Americas. The second wave was considered the most contagious, virulent, and deadly, and caused approximately 90% of the total fatalities. Subsequent waves in the springs of 1919 and 1920 saw the gradual petering out of the virus. Worldwide deaths are estimated at somewhere between 55 to 100 million people, or approximately 2.5% to 5% of the global population. The Spanish Flu pandemic claimed approximately 55,000 people in Canada, which was almost as many Canadians, some 60,000, who were killed in the First World War.

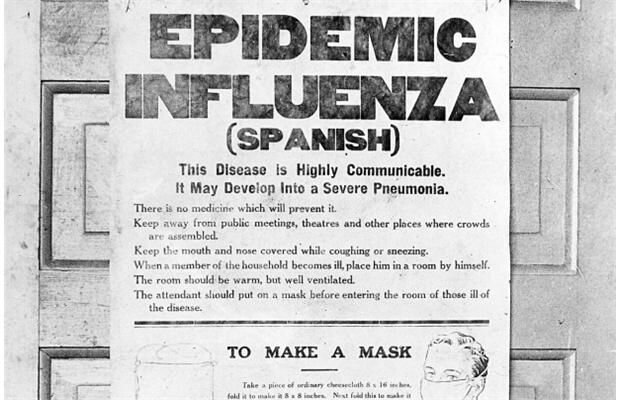

Doctors were at a loss as to what to recommend; many urged people to avoid crowded places, while others suggested their own medicinal remedies such as a combination of cinnamon, wine and beef broth. At one point aspirin was recommended, but unregulated doses may have hurt more people than it helped. Almost universally, however, the medical community advocated for the waring of masks. Doctors also told people to keep their mouths and noses covered in public.

In the late fall and early winter in 1918, normal life in Canada all but shut down. Schools, churches, theatres, places of gatherings, and public offices were all shut down. Businesses were disrupted. Although not directly enforced, most followed the recommendations. Even the Stanley Cup final, being played in Seattle in March of 1919, was cancelled. Daily life restarted in fits and spurts in the spring and summer of 1919.

In 1918, our overwhelmed local Medical Health Officer was Doctor Austin Howard McFadden (1880-1930) of Cooksville, and his directives, often given in consultation with other local doctors, appeared in local newspapers such as the Streetsville Review. We can see in the historic newspapers that the measures we are seeing today, such as social distancing and school closures, are not new. Doctor McFadden prohibited all public gatherings, the closures of churches, schools, libraries, lodges, theatres and any places of recreation on October 31, 1918. But try as he might, without a guiding hand at the Federal level to direct the overall response, the recommendations came too late to really stem the tide of the virus. Although it is too early to draw firm comparisons in the responses to the Spanish Flu to COVID-19, preliminary analysis would suggest that the coordinated Federal, Provincial and Municipal responses were more effective and more expedient than they were 100 years ago.

Unlike today’s pandemic, the Spanish flu hit hard and fast, with many dying within a days of realizing they had been infected. And as scary as COVID-19 is, we can perhaps draw a small measure of comfort in the thought that this kind of thing has happened before, and collectively we seem better prepared and mobilized, and the medical community has greater tools and knowledge at their disposal, to meet the threat today than we were 100 years ago. COVID-19 is a long way from over, and the parallels to the Spanish Flu are obvious, but this too shall pass and a new normal will, in time, emerge.