Remembering Mississauga's Christmas Past - The Great Depression

/December 3, 1931, Streetsville Review.

If you wandered through historic Mississauga during December of the 1930s, you would not hear the clatter of shopping bags or see store windows bursting with toys. This was the Great Depression, a time when families in Clarkson, Cooksville, Port Credit, Streetsville and elsewhere in historic Mississauga, were finding as many ways as possible to save money where they could. And yet, somehow Christmas still arrived with brightness, creativity, and more than a little homemade sparkle.

Mississauga in the 1930s was not the city we know today. It was a patchwork of tight-knit villages surrounded by farmland, where neighbours knew each other, and knew everyone’s problems. Jobs were scarce, wages were thin, farmers struggled to sell crops, and many people came home with empty hands. But come December, the whole community swung into holiday mode. This was the season of the frugal inventive, “let’s make it work” kind of holiday mode that only dark times could evoke.

December 10, 1931, Streetsville Review.

Local newspapers such as The Streetsville Review and Port Credit News declared that it was “never too early” to plan your Christmas decor, suggesting that a vivacious colour scheme would distract from the ongoing economic gloom. Holly was said to provoke “excitement,” while mistletoe green restored “energy” and kept a family’s spirits high. Families were warned to keep their greenery far from “naked lights,” as early electric bulbs plus wooden houses could create the kind of excitement that no one wanted.

Although the times were difficult, people still found ways to make their homes shine with Christmas cheer. One article offered instructions for making “very inexpensive trim” by saving scraps of white and silver paper, cutting them into uneven fringes, and tying them around the tree. In addition, adding anything sparkly such as glass buttons, old beads, and anything the sewing tin had to offer could become part of the Christmas tree masterpiece. And, in a stroke of creativity, families were advised to place two electric fans on either side of the tree so the paper fringe would flutter like fairy lights.

From the December 17, 1931, Streetsville Review.

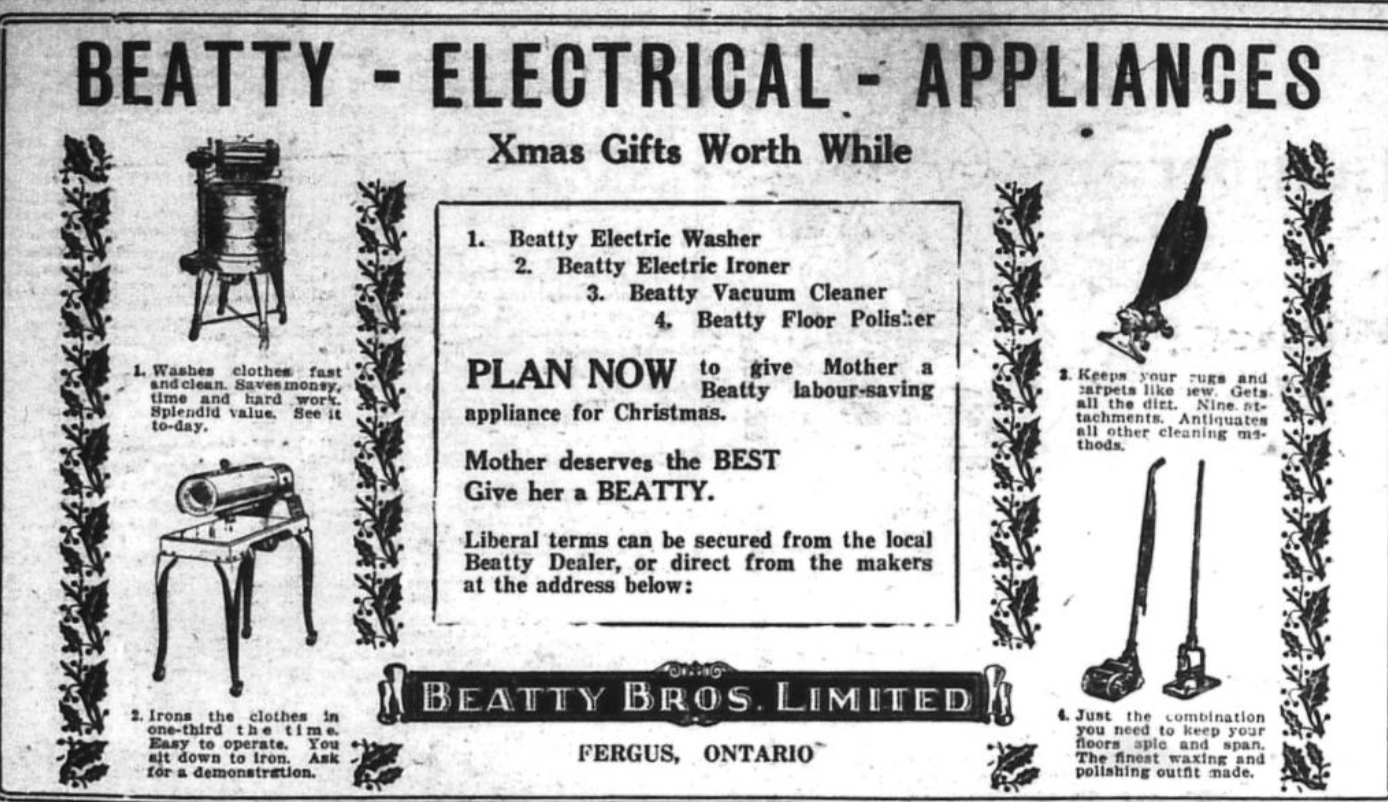

Gifts reflected the era’s practicality. Stores advertised lamps, kettles, blankets, vacuums, and sturdy winter boots as ideal presents. A new lamp meant a family could gather safely around its glow rather than rely on dim candles. A kettle was a practical blessing in homes where hospitality mattered even in hard times. A new pair of boots were essential for children walking miles along snowy concession roads. These were not stocking stuffers; they were necessities advertised and disguised as holiday cheer.

During this time, children often received one modest toy, sometimes carved or sewn by hand, and their coveted candy bags from the church. A real luxury at the time was delicious foods and treats. A cheerful column titled “Christmas fruits” explained, with great enthusiasm, where dates, currents, and Brazil nuts came from, as though readers were encountering them for the very first time. Although it might not seem like a luxury today, for many it was. Imported fruits were rather expensive, and many families either could not afford them or saved for weeks to purchase a handful of raisins for a holiday pudding or bag of mixed nuts. Oftentimes, fruits such as oranges were placed in stockings as a holiday treat.

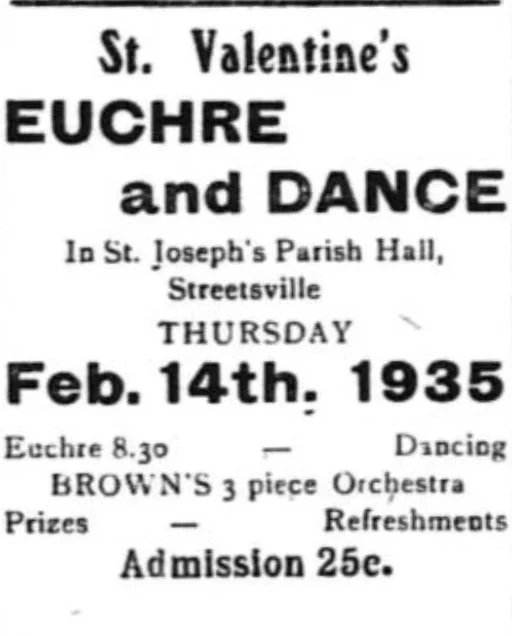

Entertainment, too, required imagination. Instead of expensive outings, the holiday fun happened at home, around the dining room table with family and friends. The local newspapers printed detailed instructions for party tricks, such as making a needle float in water, catching coins off the back of your hand, lifting a grown man using only fingers, and identifying a secretly chosen object with the help of cigar smoke. There were also tricks with strings, matches, bottles, and buttons, which were generally easily accessible and often found in the home. These tiny tricks, performed under lamplight, filled living rooms with laughter and joy – both necessities for good Christmas cheer!

Woven among the ads for boots and household goods were dedicated moments for peace and grace. Newspapers often published Christmas poems offering gentle, reflective reminders of hope. One poem, “Christmas Eve” in The Streetsville Review in December 1931 by Phyllis Hartnoll, described moonlight falling on fields and stars “like candles on a Christmas tree,” imagining every small village as its own Bethlehem. In a decade marked by hardship, the message was meant to evoke peace, optimism and renewal.

Moreover, during this time, Christmas spirit during the Great Depression was not found in decorations, gifts, or tricks. It was found in a community. Churches ran hamper drives, Women’s Institutes organized clothing collections, neighbors delivered coal or food quietly to doorsteps. Social columns advertised help for families in need: Christmas built from generosity and creativity.

During times of want, what people in historic Mississauga may have lacked, they made up for with imagination and heart. Scraps of paper became decorations. Spare coins became ingredients for pudding. A flick of the wrist became a parlour trick. A single bright star in a poem became hope for the coming year. Christmas spirit and community support were what mattered most.